This book includes articles written on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of Tunisia’s independence (1956 – 2006) and published in the Tunisian Truth magazine from 2006 to 2008, during which it covered the first years of independence 1956 – 1963 in which the national state was built and the political authority and the state supported the party. The writer enriched the second edition, which was issued after the revolution, in 2012, with what was difficult to publish in the regime of former President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

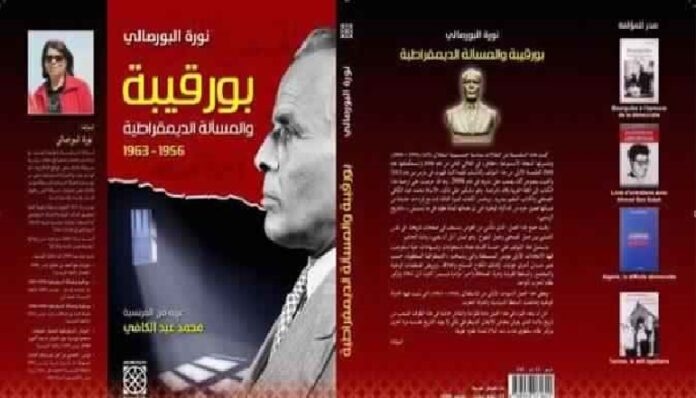

The writer is Nora Borsali. She was born on August 19, 1953 and died on November 14, 2017. A Tunisian academic, journalist, writer, literary and film critic. She is also a trade unionist, human rights activist and figure of Tunisian feminism.

In this book, the writer tried to deepen a part of the national memory that was neglected in the “official history of the Tunisian state, by combining journalistic work with the work of a historian as well as armed struggle, the taming of national organizations, society, individual authority, freedom of the press, the December 1962 conspiracy, and the establishment of a one-party system.

In her book, Noura Borsali asks about the reason for the absence of the democratic issue in the politics of the Tunisian leader, Habib Bourguiba, despite his modernization project, and despite the fact that Tunisia knew political and association pluralism, as well as freedom of expression in the early years of independence (until 1963), and she points out Tunisia’s failure to establish a democratic system when building a national state, even though it is a small country in size and population, and despite its characteristics that help and allow the democratic system.

Borsali also discussed the issue of the independence state wasting its opportunity to be a model and a democratic example to be followed by the countries of the Arab and Islamic worlds.

By answering these questions, she showed that at the political level, it is not possible to return to “Bourguibism”, which some of them advocate in this transitional period of Tunisia’s modern history, and that “Bourguibism” cannot be an alternative or an example to follow.

She cited the exploitation of Habib Bourguiba, the former president of the Republic of Tunisia, of the failed coup attempt that occurred in 1962 to abolish all freedoms and prevent all parties and associations from activity and to impose once and for all the one-party system, one opinion and one position.

After an introduction entitled “Democratic Transition: Is it the Return of Bourguiba?” In the preface entitled Authoritarian Democracy, Noura Al-Borsali tackled in the five parts of the book the topics of the first independent elections in Tunisia, the hegemony of the new constitution, independence and armed resistance: “Fallaguah” (armed resistants), the taming of national organizations and society, individual authority in the press freedom test, the December 1962 conspiracy, and the One-party tragedy.

The writer concluded her research, which contains many rare photos, documents, and valuable living testimonies, with a humane literary text entitled “We and Bourguiba: Confusion of Feelings.”

This section was filled with emotions and ambiguous feelings towards this man whose image dominated the lives of Tunisians, whether when he was the ruler of the state or when he was removed and also after his death, and even after January 14, 2011.

In this section, the writer says, on page 256, that Bourguiba imposed himself through television, radio and direct meetings with the Tunisian people: “As a complex figure, he charmed us and alienated us at the same time. An undisputed tyrant, but an ‘enlightened’ one who can only imagine power as absolute, while laying the foundations of a modern state.”